Possible, but tricky: carbon pricing in the building sector

February 28, 2020

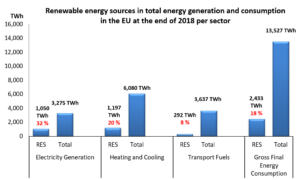

Whether to include the building sector in the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) was one of the key questions discussed at a workshop in Brussels in late January. Representatives from industry associations said at the event, organised by the European Heating Industry (EHI) association, that governments should remain in charge of the built environment and not shift all responsibility for mitigating emissions onto consumers. Staff members of the German consultancy Agora Energiewende then explained how tricky it has been to create policy based on Germany’s new carbon pricing scheme, which will take effect at the beginning of 2021 and raise the price of fossil fuels used in cars and buildings. Image: Agora Energiewende

Femke de Jong, Climate and Energy Manager at the European Insulation Manufacturers Association, also known as Eurima, said during the workshop that it “took a long time to make the ETS effective. If we now incorporate the building sector into it, we will end up with a complex and time-consuming system, and this might take attention away from more effective short-term measures.” She suggested that policymakers “focus on how to trigger a wave of renovations across Europe, the aim being to thoroughly renovate and modernise a significant number of buildings.”

Emissions trading versus energy tax

Nicola Rega, Energy and Climate Change Director of the Confederation of European Paper Industries (CEPI), said that ETS “is all about monitoring, reporting and verification”, but added that the success of the scheme will also depend on choosing the right target group. “You can either target millions of building owners or you put the energy supplier in the lead on reporting.”

In the case of the new emissions trading system for transport and heating fuels in Germany, the choice fell on the latter. If all goes as planned and the ETS is implemented in Germany in 2021, it will be the fossil fuel suppliers and distributors that will be affected, not the building owners. As a result, about 4,000 companies are expected to participate in emissions trading, according to the presentation given by Andreas Graf, Project Manager at Agora Energiewende.

In the lead up to the above, the consultancy recommended adding carbon fees to existing energy taxes as a quick and easy path to introducing a carbon price. At EU level, the European Tax Directive could turn out to be a key tool for implementing CO2 taxation across Europe.

In Germany, diverging views among members of the country’s governing coalition have paved the way for a different pricing structure. While the Social Democrats (SPD) had been pushing for the introduction of an energy tax, the Christian Democrats (CDU) favoured emissions trading at market prices. In the end, the parties reached a compromise which incorporates both ideas and consists of multiple phases:

- In phase 1, between 2021 and 2026, carbon prices will increase by a fixed amount, ranging from EUR 25 per tonne in 2021 to EUR 55 per tonne in 2025.

- In 2026, auctions will be held to sell emission certificates at prices of between EUR 55 and EUR 65 a tonne.

- In phase 3, which starts in 2027, prices will be set by the market; the decision of whether to specify a range for them will be made in 2025.

| National emissions trading scheme | Energy tax | |

| Description | Issues a limited number of emissions certificates for the transport and heating sectors. The price for each is determined by the market based on scarcity. | Adds a carbon pricing component to existing energy taxation and raises prices for petrol, diesel, natural gas and heating oil. |

| Advantages

|

Can be used for directly regulating emissions from heating and transport | Easy and quick to implement |

| Disadvantages | Complex as well as time-consuming (requires new regulations, auction platforms and monitoring) | Does not place absolute caps on emissions from burning transport or heating fuel |

| Requirements | Open communication and the use of revenue from carbon pricing to support low-income households and support climate protection measures | |

Benefits and drawbacks of implementing emissions trading or an energy tax in Germany

Source: Agora

Germany as a role model

Agora believes that the agreement on fixed CO2 prices in the first several years until 2025 should be taken as a positive sign. The little time allocated for its implementation in Germany took many observers by surprise, since a tax on fossil fuels had already been a controversially discussed topic between 2011 and 2015, at which point the German government decided to abandon the idea.

“The new announcements about carbon pricing in Germany are sending the clear message that fossil fuels will become more expensive over time,” said Graf. “However, the CO2 price set for 2021 is still too low to change the behaviour and investment decisions of consumers significantly,” he added. In Agora’s view, a price above EUR 45 per tonne of CO2 emission equivalent should have been set right from the start to support the retrofit of heating systems. Regarding road transport, a CO2 price of as much as EUR 217 per tonne will be needed to meet the EU’s 2030 climate targets, said Jo Dardenne, Aviation Manager at Transport & Environment, a Brussels-based NGO.

In a news article posted to the German-language SHK-journal.de website on 12 January, it was calculated that the owner of a building that has 150 m2 of living space, features average insulation and has been equipped with a fuel oil boiler has to pay an additional EUR 1,200 between 2021 and 2025.

Still, some aspects of the German carbon pricing scheme could serve as a model for similar schemes in other European member states, according to Graf, particularly because the government was open about the purpose for which revenues would be used and in what way parts of the population would be compensated financially.

Generally speaking, consumption taxes are regressive: they have a greater impact on lower-income households. This makes a progressive redistribution of carbon price revenues necessary. Agora also said that people are more accepting of carbon prices if the revenue from them is used to fund climate action programmes, as will be the case in Germany. By contrast, the French government did not provide a good enough explanation of where the revenue generated from its carbon tax was going to go, so the public did not believe that the additional fees were used to protect the climate.

Organisations mentioned in this article: